Key Takeaways

- Many states offer small estate shortcuts that allow assets to transfer without full probate when the estate's value falls below a state-specific dollar threshold

- Eligibility depends on calculating probate assets correctly, only individually owned assets with no beneficiary designations typically count toward the limit

- Thresholds vary widely by state, ranging from $10,000 to $200,000 or more, and each state has different rules about what assets qualify

- Using a small estate affidavit when the estate doesn't actually qualify can result in rejected filings, delays, and the need to start over with full probate

- Legal confirmation is critical before relying on simplified procedures, as asset classification and state-specific requirements are complex

{{blog-cta-legal}}

What Is a Small Estate Procedure?

A small estate procedure is a legal shortcut that allows certain estates to bypass formal probate court proceedings. Instead of opening a full probate case that can take 12 to 18 months, an executor or heir may use a small estate affidavit, a sworn statement filed with institutions or the court to collect and transfer assets directly.

Depending on your state's specific rules, this simplified process may allow banks to release funds directly to heirs without court supervision, vehicle departments to retitle cars without probate orders, and certain other assets to transfer with minimal or no court involvement.

These procedures exist to reduce the burden on courts and families when estates are straightforward and modest in value. However, they only work when the estate meets very specific criteria that vary significantly from state to state.

Understanding whether your situation qualifies requires careful calculation of asset values and proper classification of which assets count as "probate assets" versus those that pass outside probate automatically.

When Small Estate Procedures Apply

Small estate procedures typically become available after someone dies with limited assets and no complex estate planning structures. The key factor is whether the total value of probate assets falls below your state's threshold.

Timing matters when considering these shortcuts. You need to evaluate eligibility after you've completed an initial inventory of assets but before you invest time and money opening formal probate. Making this determination early prevents wasted effort if you later discover the estate doesn't qualify.

Some states impose waiting periods requiring a certain number of days to pass after death before you can use a small estate affidavit. Others allow immediate filing. These procedural variations make it essential to research your specific state's rules or consult with a probate attorney familiar with local requirements.

What You'll Need

Before evaluating whether your estate qualifies for simplified procedures, gather comprehensive information about the deceased's assets and debts.

Create a detailed estate inventory listing all assets with estimated values. Include bank accounts, investment accounts, real estate, vehicles, and personal property. Note how each asset is titled, solely in the deceased's name, jointly with someone else, or with beneficiary designations.

Research your state's small estate rules to understand the current dollar threshold and specific requirements. Many state court websites publish information about simplified probate procedures, or you can consult resources like your state bar association's website.

Obtain your state's official small estate affidavit form if one exists. Some states provide standardized forms while others allow executors to draft their own sworn statements following statutory requirements. Having the actual form helps you understand exactly what information and documentation you'll need to provide.

A reasonably complete and accurate inventory is essential before making any eligibility determination. Guessing at values or missing assets can lead you to pursue simplified procedures when full probate is actually required.

Step 1: Check Your State's Small Estate Limit

Start by identifying the current small estate threshold in the state where the deceased lived at the time of death. This is typically the state where probate would be filed, though some states have different rules for real property located within their borders.

Small estate limits vary dramatically by state. California allows simplified procedures for estates under $184,500 in 2024. Texas sets the threshold at $75,000 for real property or $50,000 for personal property. Florida allows summary administration for estates under $75,000. New York permits small estate affidavits for personal property under $50,000. Some states set limits as low as $10,000 to $25,000.

When reviewing your state's rules, confirm several critical details. First, verify the exact dollar limit, which legislatures adjust periodically for inflation. Second, determine whether the limit applies only to probate assets or to all assets combined, most states count only probate assets, but some include everything.

Check for special requirements that may apply. Some states mandate waiting periods ranging from 30 to 45 days after death before you can file a small estate affidavit. Many states exclude real estate entirely from small estate procedures, meaning any ownership of real property disqualifies the estate regardless of value. Other jurisdictions allow limited real estate under specific conditions.

These rules change over time as legislatures update statutes, so always verify current law rather than relying on outdated information. State court websites typically provide the most current thresholds and requirements.

Step 2: Calculate the Value of Probate Assets

The most critical and complex step is accurately calculating which assets count toward your state's small estate limit. This requires understanding the difference between probate assets and non-probate assets.

Probate assets typically include individually owned bank and investment accounts with no payable-on-death or transfer-on-death beneficiary designations. Real estate titled solely in the deceased's name usually counts, though some states exclude all real property from small estate calculations. Vehicles titled only in the deceased's name are probate assets. Personal property like furniture, jewelry, and collectibles that don't pass by title or beneficiary designation also counts.

Assets commonly excluded from the probate estate calculation include life insurance policies with named beneficiaries, these pass directly to beneficiaries outside probate. Retirement accounts like IRAs and 401(k)s with designated beneficiaries also bypass probate. Assets held in revocable living trusts belong to the trust, not the probate estate. Property owned jointly with the right of survivorship automatically passes to the surviving owner. Bank accounts with POD or investment accounts with TOD designations transfer directly to named beneficiaries.

Once you've classified each asset properly, total only the probate assets. If the probate estate value exceeds your state's limit, full probate is likely required regardless of how much wealth passes outside probate through beneficiary designations or joint ownership. If the probate estate falls under the threshold, simplified procedures may be available.

Because asset classification involves legal interpretation and the consequences of getting it wrong are serious, a probate attorney should confirm your calculation before you proceed. What seems straightforward can become complicated, for example, some jointly owned property may be partly probate assets depending on contribution to purchase and state law.

Step 3: Use the Small Estate Procedure If Eligible

If your estate qualifies for simplified procedures based on accurate asset classification and your state's current threshold, you can proceed with filing a small estate affidavit.

Complete your state's official small estate affidavit form or draft a sworn statement that meets statutory requirements. The affidavit typically includes the deceased's name and date of death, a statement that the estate value is under the state threshold, a list of all known assets and their values, identification of heirs or beneficiaries entitled to receive assets, and your sworn statement that the information is true and accurate to your knowledge.

Follow your state's specific filing rules, which vary considerably. Some states require filing the affidavit with the probate court before using it to claim assets. Others allow you to submit the affidavit directly to institutions holding assets, like banks or the Department of Motor Vehicles, without any court filing. Still others use a hybrid approach requiring court filing for some asset types but direct presentation for others.

When institutions accept the affidavit, they'll release assets according to your state's procedures. Banks will transfer account funds to entitled heirs. The DMV will retitle vehicles. Investment firms will transfer securities or liquidate accounts for distribution.

Keep meticulous records of this process. Make copies of every affidavit you file, save proof that institutions accepted the affidavits and transferred assets, and document how assets were distributed to heirs. These records protect you if questions arise later about your handling of the estate.

Common Challenges with Small Estate Procedures

Several issues frequently complicate attempts to use simplified probate procedures. Understanding these challenges helps you avoid costly mistakes.

Some states have different thresholds for different asset types. Real property might have one limit while personal property has another, creating confusion about what the estate qualifies for. Executors frequently struggle with probate versus non-probate classification, particularly with jointly owned property or accounts that have informal beneficiary arrangements.

States often offer multiple simplified options with different requirements. California, for example, has several abbreviated procedures depending on estate value and asset types. Choosing the wrong procedure wastes time and may require starting over.

Real estate ownership unexpectedly disqualifies many estates from simplified procedures. Executors assume their small estate qualifies until they realize even a modest home requires full probate in their state.

Financial institutions sometimes resist small estate affidavits, especially when bank employees are unfamiliar with the procedure. You may need to educate institution staff about state law or escalate to supervisors who understand these transfers.

Assets discovered after you file a small estate affidavit can push the total value over the limit, forcing a transition to full probate. This is particularly frustrating when you've already distributed some assets based on the affidavit and must now consolidate everything back into a formal probate estate.

Why Accuracy Protects You

Small estate procedures only work when applied correctly according to strict legal requirements. As the person filing the affidavit, you're swearing under oath that the information is accurate.

You must correctly identify which assets are probate assets versus non-probate, apply the correct state threshold to the right category of assets, and use the appropriate forms and filing methods for your jurisdiction. Getting any of these wrong can result in rejected affidavits that institutions refuse to accept, significant delays while you correct errors and refile, and potential personal liability if you improperly distribute assets without proper authority.

Courts and institutions rely on the accuracy of your sworn statements. If you misrepresent the estate's value or asset composition, even unintentionally, you may face legal consequences. In extreme cases, beneficiaries who receive less than entitled due to procedural errors might have claims against you personally.

Careful review by a probate attorney before filing protects both the estate and you personally. The cost of a few hours of legal consultation is far less than the expense of correcting mistakes or defending against claims later.

Timeline and What to Expect

When a small estate affidavit works properly, it dramatically shortens the timeline for settling an estate. Traditional probate takes 12 to 18 months or more. Simplified procedures can sometimes resolve in weeks or a few months.

The actual timeline depends on your state's requirements and how quickly institutions respond. States with mandatory waiting periods require 30 to 45 days after death before you can even file. Preparing the affidavit and gathering supporting documentation takes 1 to 2 weeks. Filing with the court (if required) and obtaining approval adds another 2 to 4 weeks in many jurisdictions.

Presenting affidavits to institutions and waiting for them to release assets can take anywhere from a few days to several weeks per institution. Some banks process these quickly while others require legal department review. Collecting all assets and distributing to heirs adds another 2 to 4 weeks.

Overall, successful small estate procedures typically complete in 2 to 4 months compared to 12 to 18 months for full probate, a significant time savings when the estate clearly qualifies.

Conclusion

Small estate procedures can save significant time and expense, but only when the estate clearly qualifies under your state's specific rules. Because thresholds vary widely and asset classification is technically complex, careful evaluation is essential before relying on these shortcuts.

By confirming your state's current limits, accurately calculating probate asset values, understanding which assets count toward thresholds, and verifying eligibility with a probate attorney, you can confidently use simplified procedures when appropriate while avoiding costly mistakes.

The key is recognizing that small estate affidavits are powerful tools when used correctly but can create serious problems when applied to estates that don't actually qualify. Taking time to verify eligibility upfront prevents wasted effort and protects you from liability.

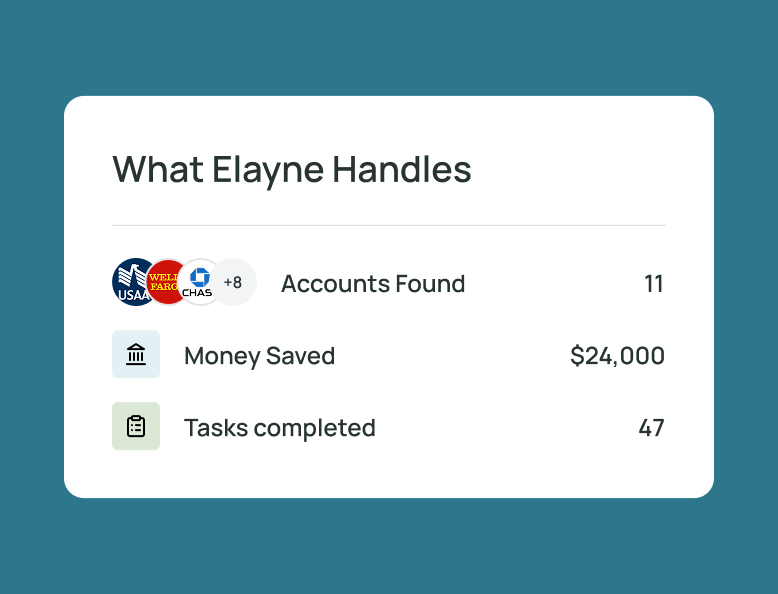

If researching state rules, classifying assets correctly, and navigating affidavit requirements feels overwhelming while you're also grieving, Elayne's platform can help coordinate eligibility review, organize documentation, and guide you through proper procedures as part of structured estate administration.

{{blog-cta-legal}}

FAQs

Q: Does owning real estate automatically disqualify a small estate?

In some states yes, while other jurisdictions allow limited real estate under the small estate threshold or have separate procedures for real property.

Q: Can I switch to full probate later if needed?

Yes, if you discover the estate doesn't qualify after filing a small estate affidavit, but this requires amended filings and may delay the process significantly.

Q: Should I rely on online summaries of small estate limits?

No, always confirm current rules with official state sources or consult a probate attorney, as limits change periodically and online information may be outdated.

Q: What happens if I use a small estate affidavit incorrectly?

Institutions may reject your affidavit, forcing you to open full probate, and you could face personal liability if you distributed assets without proper authority.

Q: How do I know if an account has a beneficiary designation?

Contact the financial institution directly with your death certificate and executor documents to request beneficiary information for each account.

Q: Can I use a small estate affidavit if there's a will?

Yes in most states, as long as the probate assets fall under the threshold, having a will doesn't automatically require full probate.

**Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not provide legal, medical, financial, or tax advice. Please consult with a licensed professional to address your specific situation.