Key Takeaways

- Executors have a legal duty to conduct a thorough search for all bank and investment accounts, including small, dormant, and online-only accounts

- Financial accounts are often spread across multiple institutions with different ownership types (sole, joint, POD, trust) that determine whether they go through probate

- Start by reviewing mail, email, and recent tax returns to build an initial list, then contact each institution to confirm all accounts tied to the deceased's name and Social Security number

- Missing accounts can delay probate, create tax filing issues, and expose the executor to liability for incomplete estate administration

- A centralized account inventory becomes your working document for probate filings, tax preparation, and final accounting

{{blog-cta-financial}}

Why Finding All Financial Accounts Matters

Bank and investment accounts form the backbone of most estates. These balances directly affect whether probate is required and how complex it will be, estate and income tax reporting, how much cash is available to pay creditors and expenses, and what remains for distribution to beneficiaries.

Courts, taxing authorities, and beneficiaries rely on you to present a complete and accurate picture of the estate's financial assets. Taking a careful, methodical approach protects the estate and reduces your risk of delays, disputes, or personal liability.

Executors are expected to make a reasonable, good-faith effort to locate every account. This includes accounts the deceased rarely used, forgot about, or managed entirely online. Missing accounts that surface later can force amended court filings, corrected tax returns, and uncomfortable explanations to beneficiaries who thought the estate was settled.

When This Step Happens in Estate Administration

Gathering bank and investment accounts typically happens early in the probate process—after you've been appointed executor but before you file detailed inventories with the court or prepare tax returns.

This financial discovery sets the foundation for everything that follows. You can't accurately complete probate court filings, calculate estate taxes, or determine what's available for distribution until you know what accounts exist and what they're worth.

Many executors underestimate how time-consuming this detective work becomes, especially when the deceased managed finances privately or accumulated accounts over decades without consolidating them.

What You'll Need

Before you start searching, gather several key items that will help you identify accounts more efficiently.

You'll need multiple certified copies of the death certificate. Financial institutions require these before releasing any information. Your executor or administrator documents: Letters Testamentary, Letters of Administration, or Small Estate Affidavit, prove you have legal authority to access account information.

Review recent mail and email carefully, looking for bank and brokerage statements, "your statement is ready" email notifications, and any correspondence from financial institutions. Many people now receive paperless statements, so email is often more revealing than physical mail.

Pull tax returns from the last 2 to 3 years. These documents reveal account holdings through interest income reported on Schedule B (indicating bank accounts, CDs, or savings bonds), dividend income showing investment accounts, and capital gains from securities sales pointing to brokerage accounts.

Set up a simple tracking system, a spreadsheet, notebook, or estate management platform, where you'll record every account as you discover it. Having these materials organized before you start contacting institutions reduces repeated outreach and confusion.

Step 1: Build an Initial Account List

Start with a broad review of all available records. From mail, email, and tax documents, create a list of every financial institution that sent communications or reported income.

Include different account types in your search. Banking accounts encompass checking accounts, savings accounts, certificates of deposit, and money market accounts. Investment accounts include brokerage accounts, managed investment portfolios, and dividend reinvestment plans. Don't forget retirement accounts like IRAs, 401(k)s, 403(b)s, pensions, and annuities, while these often pass directly to named beneficiaries outside probate, you still need to identify them for tax purposes and to verify beneficiary designations.

For each account you identify, note the institution name, account type, last four digits of the account number if you have it, and approximate last-known balance based on statements or tax forms. At this early stage, completeness matters more than precision. You're building a starting point that you'll verify and expand through direct contact with institutions.

Many people hold accounts at institutions they haven't visited in years. Look for old statements in filing cabinets, desk drawers, or boxes of financial paperwork. Check email going back several years for electronic statement notifications.

Step 2: Confirm Accounts with Each Institution

Next, systematically contact each bank, credit union, and brokerage on your initial list. This verification step is crucial because many people hold multiple accounts at the same institution, and some accounts may not have appeared in recent statements.

When calling or writing to each institution, explain that the account holder has died and identify yourself as the executor or administrator. Be prepared to provide a certified death certificate and your executor documentation if they request it.

Ask the institution to search their system for all accounts associated with the deceased's name and Social Security number. This catches accounts you didn't know about, old savings accounts, forgotten CDs, or investment accounts opened decades ago.

Request confirmation of the ownership structure for each account. This determines whether the account goes through probate or passes directly to survivors. Sole ownership means the account is part of the probate estate. Joint ownership with rights of survivorship typically passes automatically to the surviving owner. Payable-on-death (POD) or transfer-on-death (TOD) designations allow accounts to bypass probate and go directly to named beneficiaries. Trust ownership means the account belongs to a trust and follows the trust's distribution rules.

Also ask for the date-of-death balance or instructions for requesting official date-of-death valuation statements. You'll need these exact figures for court filings and tax returns.

This step is informational only. Don't move, withdraw, or close any funds until you've confirmed ownership structure and your legal authority to act. Closing accounts prematurely or distributing joint account funds can create serious legal problems.

Step 3: Create a Master Account Inventory

As confirmations come in from various institutions, consolidate everything into a single master inventory. This becomes your central reference document throughout estate administration.

For each account, record the institution name and account type, last four digits of the account number, ownership or beneficiary status (sole, joint, POD, trust), date-of-death value or note that it's still pending, and any important notes about next steps, such as whether you've requested official valuation statements, if a joint owner is involved, or if POD beneficiaries have been notified.

This inventory feeds directly into probate inventories and appraisals you file with the court, estate and income tax filings, evaluations of how much is available to pay creditors, and calculations of what remains for distribution to beneficiaries.

Keep this document updated as new information arrives. You'll refer to it constantly over the coming months, and your probate attorney and accountant will need copies to prepare required filings.

Step 4: Watch for Accounts That Surface Later

Even with diligent searching, additional accounts often appear after you think you've found everything. This is normal and manageable as long as you respond promptly when new information surfaces.

Stay alert for new mail that arrives after you've set up mail forwarding. Financial institutions may continue sending statements to the deceased's address for months. Tax forms arriving in January and February, particularly 1099-INT for interest income, 1099-DIV for dividends, and 1099-B for investment sales, reveal accounts you might have missed.

Statements from unfamiliar institutions sometimes appear weeks or months after death. Unclaimed property notices from state treasurers can alert you to old accounts the deceased forgot about.

When new accounts surface, immediately add them to your inventory and notify your attorney if this affects court filings already submitted. Most courts allow amended filings when executors discover assets after initial inventories, but prompt disclosure is important.

Common Challenges When Searching for Accounts

Several issues frequently complicate the search for financial accounts. Understanding these challenges helps you prepare for them.

Online-only or paperless accounts can be nearly impossible to find without email access. If the deceased managed finances primarily through mobile apps and electronic statements, you may have no paper trail to follow. Request email access through the email provider if possible, or search the deceased's computer and phone for financial apps and saved login information.

Multiple accounts at the same institution confuse many executors. Someone might have three checking accounts, two savings accounts, and an IRA all at one bank. Don't assume one statement means you've found everything that person held there, specifically ask institutions to search for all accounts.

Dormant or low-balance accounts often get overlooked because they haven't generated statements in years. Financial institutions must still disclose them when you request a complete search using the deceased's Social Security number.

Confusion between ownership and beneficiary status creates problems when executors act too quickly. A joint account with a surviving co-owner isn't part of the probate estate, but executors sometimes freeze or try to close these accounts by mistake. Similarly, accounts with POD or TOD designations belong to named beneficiaries, not the estate.

Discovering accounts after probate filings have been submitted requires amended paperwork and explanations to the court. While courts expect some amendments as executors learn more about estates, frequent corrections suggest inadequate initial investigation.

Why Accuracy Protects You as Executor

As executor, you serve as a fiduciary, someone who must act in the best interests of the estate and its beneficiaries. This fiduciary duty requires you to conduct a reasonable and thorough search for assets, document your search efforts carefully, and act in good faith with complete transparency.

Failing to identify accounts, or acting before ownership is clear, can result in serious consequences. Courts may delay proceedings or require amended filings that cost the estate additional attorney fees. Beneficiaries may dispute your competence or accuse you of hiding assets. In extreme cases, you could face personal liability if your negligence causes financial harm to the estate.

According to the National Association of Estate Planners & Councils, executors who document their asset search efforts thoroughly protect themselves from later claims of inadequate investigation. Keep records of every institution you contacted, what you asked them to search for, and what they reported back.

Careful recordkeeping and professional guidance from your attorney are your best protections against liability. If you make a good-faith effort to find all accounts and document your work, courts and beneficiaries will recognize you fulfilled your duties even if an obscure account surfaces later.

How These Accounts Are Used Throughout Estate Administration

The account inventory you create during this initial search becomes essential throughout the entire estate administration process.

For probate inventories and appraisals filed with the court, you must list every account with its date-of-death value. Estate and income tax filings require detailed reporting of all financial assets and any income they generated after death. When evaluating creditor claims, you need to know exactly how much cash the estate holds to determine whether there's enough to pay all debts.

Distribution calculations depend on knowing the complete financial picture. Beneficiaries want to understand what exists and what they'll receive. Missing accounts discovered later can completely change distribution amounts and force recalculations after you thought everything was settled.

Errors or omissions at this foundational stage create problems that ripple through every subsequent step of estate administration. Taking the time to search thoroughly at the beginning saves you from costly corrections later.

Timeline and What to Expect

Building a comprehensive account inventory typically takes 4 to 8 weeks, though complex estates can take longer. The timeline varies based on how organized the deceased's financial records were and how responsive institutions are to your requests.

Expect some institutions to respond within a few days while others take 2 to 3 weeks to search their systems and provide confirmation. You may need to follow up multiple times with institutions that are slow to respond or that provide incomplete information initially.

The search process overlaps with other early executor duties like securing property, notifying Social Security, and meeting with your probate attorney. You don't need to complete the account inventory before starting other tasks, but you do need it substantially complete before filing probate inventories or preparing the deceased's final tax returns.

Conclusion

Identifying all bank and investment accounts is one of the most important early responsibilities in estate administration. While the process can feel like detective work, piecing together financial information from scattered statements, tax forms, and institutional records, a structured approach helps ensure nothing is missed.

By gathering available records, systematically confirming accounts with institutions, maintaining a master inventory, and staying alert for accounts that surface later, you fulfill your fiduciary duty and keep the estate moving forward. This thorough financial foundation protects you from liability and gives beneficiaries confidence that you're handling the estate responsibly.

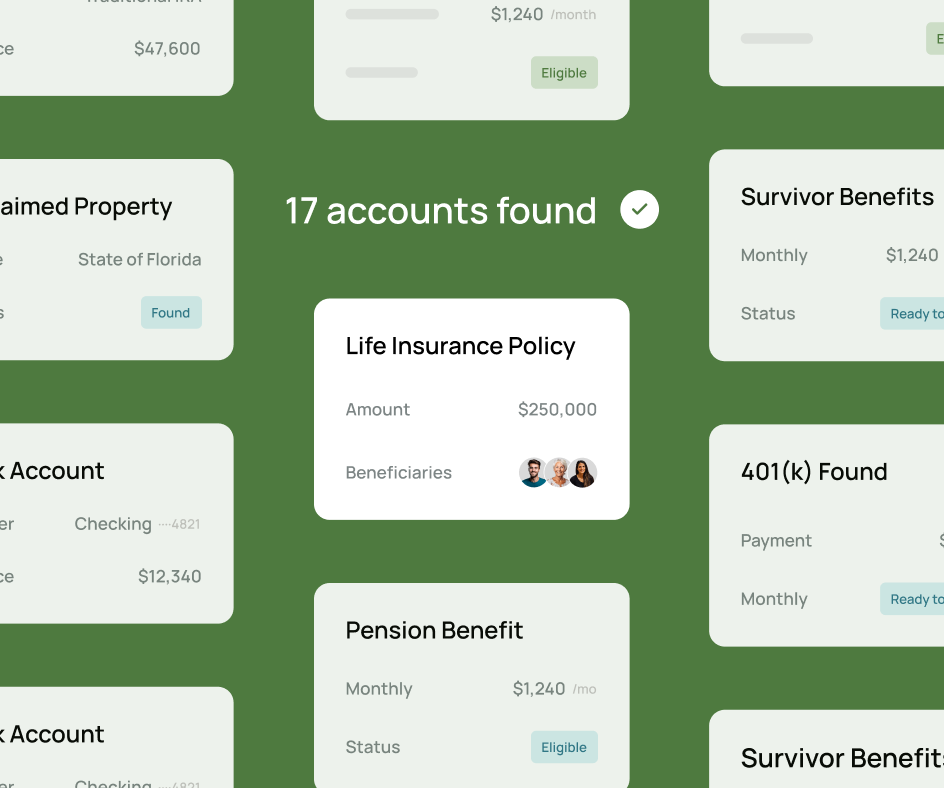

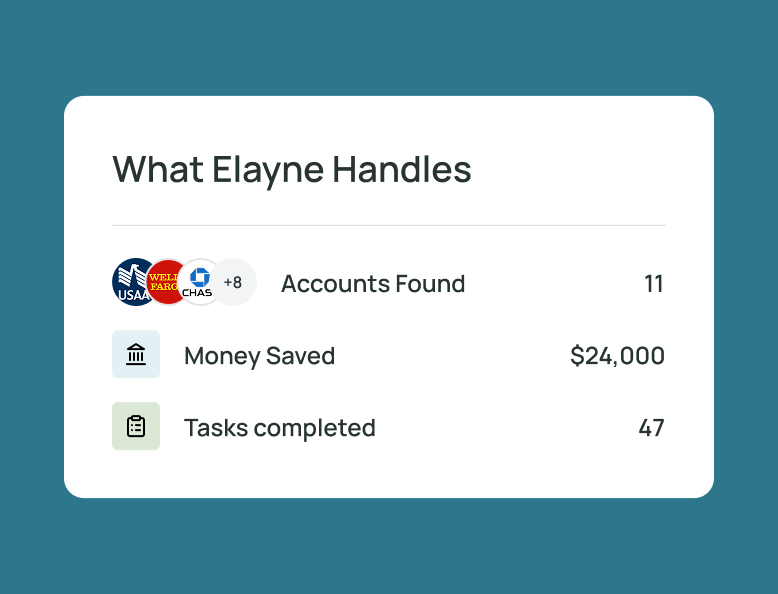

If reconstructing a loved one's financial life account by account feels overwhelming while you're also grieving and managing dozens of other executor responsibilities, Elayne's platform can help you identify, organize, and document all financial accounts so you can proceed with confidence and clarity.

{{blog-cta-financial}}

FAQs

Q: Do small or dormant accounts really need to be included?

Yes, even small balances must be disclosed in probate filings and accounted for in estate tax returns, regardless of whether the account has been active recently.

Q: What if I don't know the exact balance right away?

Use reasonable estimates based on the most recent statements and note that values are pending official confirmation from the institutions.

Q: What happens if an account is discovered later?

Most courts allow amended filings when executors discover assets after initial inventories, but you must disclose the new account promptly and explain the circumstances.

Q: How do I access online accounts if I don't have passwords?

Contact the financial institution's estate services department with your death certificate and executor documents to request access or official statements.

Q: What if the deceased had accounts in multiple states?

You can still identify and inventory them, your executor authority typically extends to assets anywhere, though some states require ancillary probate for real property.

Q: Do retirement accounts go through probate?

Usually not if the deceased named beneficiaries, but you still need to identify them for tax purposes and to ensure beneficiaries file their claims properly.

**Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not provide legal, medical, financial, or tax advice. Please consult with a licensed professional to address your specific situation.